Games are Movies, Apps are TV Shows

The life and death of games and apps greatly resembles the life and death of movies and TV shows, respectively. And at the end of the day, they're all just competing for attention on pieces of glass.

March 10, 2014

I've played Threes obsessively for the last few weeks. TouchArcade calls it a "Perfect Mobile Game", which is also how I'd describe it. But now my interest is waning and I'm nearly done with it.

Threes replaced Flappy Birds as my go-to iPhone game. Before Flappy Birds it was Wordbase, and before that Clumsy Ninja and Hatch. The list goes on: Letterpress, Dots, Draw Something, Words with Friends, and Angry Birds. The pattern is always the same — I play the game compulsively for a few weeks until I stop playing it altogether.

Games have a shelf life. We all knew Flappy Birds had one, even if the developer chose to go out on top. An excellent piece on TechCrunch about the mechanisms which relegated Flappy Birds to "fad” status portended it’s inevitable “death”:

Given the meteoric success and subsequent decline of other games like Candy Crush Saga, Angry Birds, and FarmVille, perhaps the death of Flappy Bird was more than a rash decision. Perhaps it was a mercy killing? (emphasis mine)

At the end of the post:

Had Nguyen wanted to see Flappy Birds die, all he had to do was wait. (emphasis mine)

Tech observers often use morbid hyperbole to describe the decline of once-successful products: "MySpace is Dead" and Everpix "hit the deadpool", etc. With Flappy Birds, it's not only harsh but inaccurate to say that it was going to "die". Rising and falling is what games do, like movies which enter and then exit theaters. Elysium was a popular movie this past year — would you say that Elysium "died"? Or that the movie is now "dead"?

The majority of games and movies take a long time to create but earn only a few months of attention. Sometimes the run is long enough to have made the game or movie a profitable venture, so years of massive profitability can't be the benchmark by which we measure their success (a "non-death"?).

Of course some games (Angry Birds), like some movies (Toy Story), are so transcendent that they merit sequels and plush toys. And some infinitely variable games (e.g., Minecraft, World of Warcraft) are so unique that they fail the comparison of games to movies. But consider why game makers, like movie makers, organize themselves into things we call "studios": Because they plan to make many things which will burst onto the scene and then fade out of existence.

Apps are different

Non-game developers can't afford to develop many apps that cycle in and out of relevance. I suspect most app developers think about building something to last several years to a decade, about the length of the run for a successful television show.

Like most TV shows, the majority of apps flame out within the first year. Flurry's excellent study on the "half life" of apps shows that most apps hit peak usage within the first three months.

Social apps, which are expressly designed to take advantage of network effects, are second only to Games with an average of three months before the decay starts.

There aren't any easy answers to as to how to evade the decay, though the TechCrunch post identifies a great, if unlikely, role model for app makers: Breaking Bad. Great apps, like great TV shows, are ever-evolving, always-growing, and full of re-invigorating surprises.

Another sense in which apps are like television shows is that many need a regular time and place where they'll meet their customers. Early afternoon on weekdays is a good time for soap operas, Sunday afternoons for football, Sunday evenings for serious dramas, and late on weeknights for variety shows. Runkeeper reminds me to run in the evenings, Twitter is essential for following live events, and podcasts are great for a commute. These ties are so strong that we associate the time of day and week with those types of TV shows or apps. This is even more apparent when you compare it to most games and movies, which aren't nearly as contextual.

Reluctant Entertainers

Most app makers don't think of themselves as being in the Entertainment business. From the vantage point of someone who makes Software, the Entertainment business seems flighty and Old-World-ish. App makers, myself included, like to think that we're changing the world in a way that movies and TV shows are not (even if, like movies and TV, we're mostly competing for consumers' attention).

You'd describe Line as a "messaging app". While operating at their scale requires technical excellence, their unique strength is not in their technical innovation but rather in their creativity and the immense gravity of their brand. They're a multi-platform Entertainment company that, among other things, sells branded merchandise, which describes Disney as well as it describes Line.

On the other end of the spectrum, struggling, independent developers often voice the same complaints as struggling actors, filmmakers, and musicians: They can't can't get discovered and they don't earn enough for the quality and importance of their work. Like struggling artists, there are many developers who do what they do love their craft, and in spite of the fact that it's really difficult to make a living in that business.

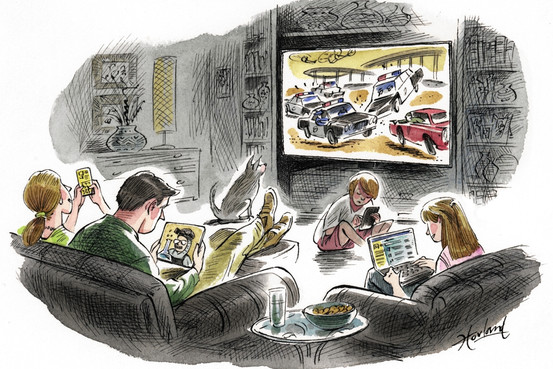

An app or game developer calling himself an "Entertainer" may not make much of an immediate impact. But as phones and devices continue to meld with how we control our TV, the lines are sure to blur even further. As Benedict Evans would say, TV's, tablets and phones are all just pieces of glass; App makers, game makers, TV show producers and movie producers — we're all just competing to be the thing you tap on the glass to consume.