Creating and playing games

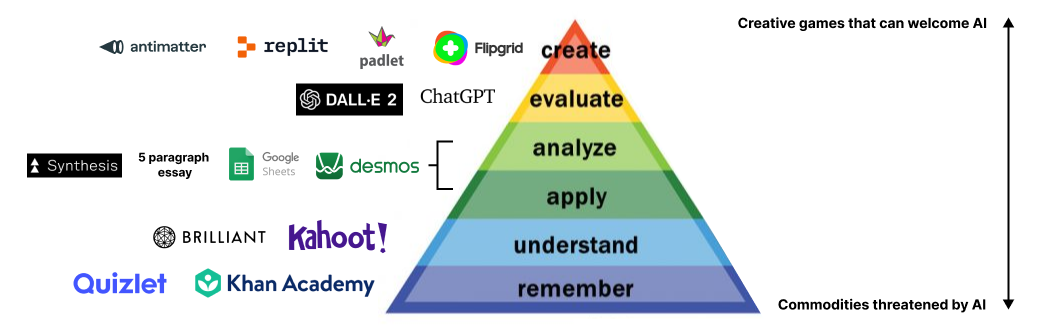

The closer a learning product is to the bottom of Bloom’s Taxonomy, the greater the risk of being commoditized by AI

Instead of insisting on top-down control of information, embrace abundance, and entrust individuals to figure it out. In the case of AI, don’t ban it for students — or anyone else for that matter; leverage it to create an educational model that starts with the assumption that content is free and the real skill is editing it into something true or beautiful; only then will it be valuable and reliable.

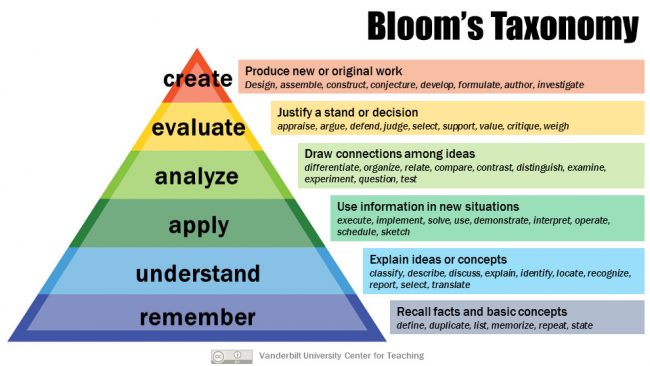

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s TaxonomyAs far as academic frameworks go, Bloom’s Taxonomy is remarkably durable and intuitive (it’s probably durable because it’s so intuitive). It's the framework through which I think all these What happens to learning in a ChatGPT world? should be viewed.

Learning products in Bloom's Taxonomy

If you take Bloom’s Taxonomy as the model for learning and plug in all of today’s tooling—now maybe including ChatGPT—you get something like this:

The closer you are to the bottom of Bloom’s Taxonomy, the greater the risk of being commoditized by AI. Paraphrasing Wikipedia on your way to a five-paragraph essay isn’t exactly new, and it’s now even easier with GPT3. It doesn’t even seem far off at all that ChatGPT could reproduce rote exercises and utilities like flashcards, coding and math exercises.

It's certainly true that creating flashcards is actually more useful than practicing with flashcards you found. This is foundational to Anki and even Quizlet—my understanding is that Quizlet's marketplace of flashcards belies the core, valuable activity of creating flashcards on your own or with friends. But we're talking human behavior here; ChatGPT flashcards are to self-made flashcards as Keurig is to roasting and grinding your own coffee beans. The former will dominate.

I think Ben Thompson mostly got it right. Evaluating whether and in what ways the AI captured the subject matter accurately is not only an interesting exercise (albeit a little contrived), it’s arguably more valuable than re-producing the material that other learners have already produced a million times over. Flashcards and exercises are commodity products that computers can generate better than humans. We simply had an interim period where some online tools helped facilitate that kind of production because the internet transforms distribution.

As Austin Allred, founder of the coding academy BloomTech (yes it's the same Bloom), pointed out yesterday, machines can accelerate all this rote learning—Remembering and Understanding in Bloom's Taxonomy terms—by enabling more people to play more games against the computer (more on that below).

In 1984 an education researcher named Benjamin Bloom found that the median student using personalized tutoring and mastery-based progression performs better than 98% of students in a traditional classroom.— Austen Allred (@Austen) December 5, 2022

Computers and AI are now making those two things cost $0.

Buckle up. pic.twitter.com/RlJGVtikGf

At the tippy top of the Taxonomy, the outlook for learning and education is arguably brighter than ever. Because all the utilities at the bottom will get commoditized, we have more time to spend in the most valuable area of learning: Creation and Evaluation. What’s more, new tools and services make Creation and Evaluation easier than they’ve ever been. Think:

-

Creating games on Replit

-

Telling authentic stories via Flip

-

Creating learning memes on Antimatter (full and shameless disclosure: I’m the founder of Antimatter)

A Cat and a Mouse

Why won’t creating games, telling stories, or creaing memes be commoditized the way exercises and utilities will? Because, let’s not forget, ChatGPT isn’t studying history so much as it’s learning from the stories that humans have told about history. Every novel story created by a human is a story that ChatGPT has yet to learn. And every story told by ChatGPT is potential raw material for humans to tell a new, novel story. We’re one step ahead by definition.

To be or not to be (intensely human)

To be or not to be (intensely human)There remains a very wide gap between AI’s ability to tell good jokes or puzzle-like stories and what humans are able to produce. This isn’t totally a coincidence. Memes are in some ways a reaction to the legibility of the internet today, the very same legibility that serves as one of the foundations of LLM’s. It’s inevitable that LLM’s will be capable of being genuinely funny or creating real puzzles, but it may be closer to the last mile than wherever we are today, and it may turn out to be an infinite cat-and-mouse game.

More Games

Speaking of games, it's my general belief that technology inevitably makes everything more game-like. Less time putzing around, more time playing measurable status games on Facebook and Twitter for Likes and Retweets or actual games on Fortnite, Minecraft, etc. Less time watching sports, more time playing fantasy sports. Less time saving with a steady APR, more time investing in markets that go up and down.

In a sense, the What happens to Learning and Education in a world where content is free and AI is abundant? question could be re-phrased in game-like terms: Students + AI vs. Education. To be clear, that's the fear ChatGPT is drumming up; it's not and never should be adversarial. Still, to that end, I think it’s instructive to look at the diverging outcomes of the two games that have been solved in some form by math.

Baseball. Math hasn't ruined baseball so much as baseball management's inertia in saving the game from the math. The math tells managers to pull starting pitchers swap relievers in and out according to their as-little-as-one-batter specialities; the math also teaches you not to steal bases and to shift infielders in ways that eliminate the mano a mano qualities that once made baseball fun to watch. Whether it's out of inertia or nostalgia, baseball's management has been dreadfully slow in adjusting the game to preserve what made it special. It's a lesson in inaction.

While chess and baseball's courses aren't diametrically opposed—baseball needs to be saved while chess naturally fits more seamlessly into the world we live in now—we're nevertheless presented with two models of dealing with the math. With respect to learning and education, we should avoid baseball's inertia and nostalgia at all costs. To reiterate Ben Thompson's point, "Instead of insisting on top-down control of information, embrace abundance, and entrust individuals to figure it out."

Similarly, we should embrace the infinite distribution of challenges that computers and the internet have brought to the world of chess. Consider how viewers of chess game streams look at the model during the game, which enhances the conversation around the game and makes everyone smarter. More liquidity, more infinite games for learners to play. There's little to fear but inaction.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯