Why Messengers

Making the case for new aggregators to deliver services that don't need apps, and why that might actually reduce the current App Store hegemony

September 28, 2015

The term "WeChat of the West" and the anticipation around the Facebook Messenger platform often lead to a few misconceptions:

- User interfaces will decline in importance as services move inside messengers

- We'll primarily interact with services over text

- Apps will recede into one dominant, hegemonic messenger

While there are elements of truth to all of these, none are entirely true.

For one, we already have one WeChat of the West: Apple. The business models are different — WeChat sells access to game-related stuff, Apple makes software to sell hardware — but they both monetize their roles as attention hogs to become distributors for lots of the good stuff one can get on a mobile phone.

It seems strange to identify Apple as a WeChat of the West because Apple does many, many more things besides messaging and software/services distribution. But between Apple's Messages app (what most still call "iMessage") and the App Store, Apple does both in a way that parallels the WeChat's distribution-through-attention model. The distribution-through-attention model isn't terribly unique, of course, but messaging is the killer app on mobile and hence that's where all the attention is.

In other words, Messages being so damn good is one of the top reasons people want to use their iPhones minute after minute, day after day, year after year. So even though Messages isn't a platform like WeChat, it serves something of a similar purpose: Usage of Apple's Messages leads to iPhone usage and loyalty, which leads to App Store usage and loyalty, which leads to further iPhone usage and loyalty. Usage of WeChat’s messaging and social networking features leads to discovery of services on WeChat which leads to usage and loyalty and so on.

Facebook wants to be a WeChat as well with Messenger. If Facebook Messenger is aiming to do much of the same things that Apple's Messages + Apple's App Store combo meal does, how or why is there room for both? The answer, I think, is that for many and maybe even most of the legitimately valuable services being created today, a native app is overkill. It may well be that the right interface for these services are smaller in scope, more (but not entirely) conversational, and more conventional than the kind of native app we've come to know since the launch of the App Store.

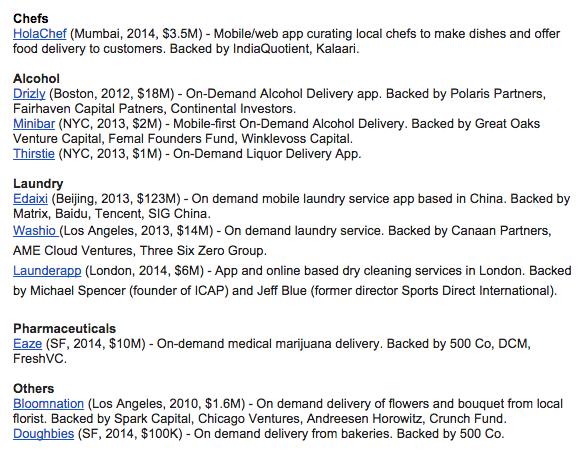

Do we really need unique apps for on-demand laundry and on-demand cookie delivery? These services are practically begging for an aggregator, whatever form it takes

Do we really need unique apps for on-demand laundry and on-demand cookie delivery? These services are practically begging for an aggregator, whatever form it takes

There's a rule of thumb that if your users aren't going to need your service once a week, you don't need to be on their springboard. Shyp, for example, is a useful service for shipping things from my home, but I ship things maybe only once a year. Is it necessary for me to have to go through all the rigamarole of installing Shyp, permission the app, learn a whole new UI, enter my credit card details, and have it loiter on Page 4 of my springboard just to use the actual service once a year? It seems much more suited for the dominant model that came to define the web: search for "ship from home", or even "Shyp", in the moment I need it and then launch the service.

There's a possible future of dynamically-delivered apps, but an aggregator of lightweight apps suits those needs very well: I’ve already permissioned the aggregator’s app to send me notifications and I can use the aggregator’s centralized payment system, so I don't have to enter in my credit card details all over again. What makes messengers particularly well-suited to serve as the next-generation of aggregator is that customer service is native to the platform. If I have a customer service question, do I want to use some unique customer service interface inside an app, or the messaging interface I'm already highly familiar with? The customer service angle is key, as the raison d’être for many apps is just as a channel for customer service:

Customer service is a major use case for mobile. [Source: FollowAnalytics via VentureBeat

Customer service is a major use case for mobile. [Source: FollowAnalytics via VentureBeat

“Five years ago, everyone wanted to have an app because … well, it was the cool thing to do. Today, every business needs an app in order to get closer to their customers and deliver effective, immediate customer service....“Customer service is the primary purpose of brands’ mobile presence,” said FollowAnalytics’ CEO Samir Addamine. “Especially in banking, insurance, retail, ecommerce, travel, hospitality, and automotive.”

This is sort of a terrible reason to have an app when you consider how much effort goes into building an app, and especially when you consider that the proprietors of the messengers, which can handle customer service natively, employ all the best engineers and build the best apps and experiences.

The most controversial thing I'll write in this post, which even I have a hard time swallowing, is that we may be arriving at an end of history when it comes to mobile user interface . We've spent the past seven years, dating back to the introduction of the App Store in iOS 2, figuring out user interaction models on the phone: Apple figured out that a grid of icons was the way to launch an app; Instagram figured out that the native way to view photos is in a feed where you can digest one photo a time; every e-commerce company converged on putting the shopping cart icon in the upper right hand corner; Tinder taught everyone that the best way to find a date on your phone is to swipe left and right through cards. And so on.

Look around your phone and maybe you'll agree that the pace of discovering new ways to do things on mobile has slowed down; user interface design is becoming increasingly homogenous; it's now virtually impossible to build a business just by figuring out the natively mobile way of doing things. You just have to build a great service that people want and then ship an app that follows convention while adding a few touches for branding.

This sets the table for Facebook Messenger or some other messenger(s) to provide those conventions for app developers. In fact, that's one of the most comforting things about a messaging interface: you type stuff in a text box on a bottom, your input shows up in a chat bubble on the right, and the responses show up in a chat bubble on the left. Facebook could presumably create a Bootstrap for Messenger apps as it extends the platform, enabling a few other highly standardized user interface elements.

While that sounds depressing to those of us who love the craft of building great software, consider how this is happening across the web already, what with every site using a big hero section with white cutout text, often on top of a photograph or silent video. Or that so many apps look so similar nowadays that many people might well think that Apple makes all the apps in the App Store. Or Telegram's bot platform, where developers can programmatically set input options as keys on a normalized keyboard. (The programmable keyboard may be the most brilliant aspect of Telegram's bot platform.) Convention often has an expansionary effect because it makes software so easy and reliable for the masses.

Telegram's easily programmable "keyboards" may be the brilliant aspect of Telegram's bot platform

Telegram's easily programmable "keyboards" may be the brilliant aspect of Telegram's bot platform

Some have made this "end of mobile UI history" argument in a different form: That the future of apps is "no user interface". I think this rendition of the argument takes it too far, and is flawed for a few reasons.

For one, there is no such thing as having no user interface. If you're like Magic or GoButler delivering concierge service via SMS, your interface is the system's interface. It's just not your own interface. This is really a matter of adopting conventions to the extreme more than it is not having any user interface whatsoever.

Two, texting is a great way to interact with services: it's light, fast, familiar and informative, especially when the system gets smart and starts converting words into data. Likwise, voice can also be a useful medium. But neither is better than a graphical user interface in a majority of cases.

Three, neither branding nor user interface are going to be subsumed entirely by messaging. If you're operating a service that is a primary use case in many people's lives, like taxi-hailing or even some new, important social medium, your icon belong on the user's springboard and you should have a great UI. Heck, if Facebook or Telegram or Kik or some other messenger platform turns out to perform so well for you that you can continue investing resources in that endpoint, and if the platform allows it, you might be wise to build a unique user interface in your messenger app (just as you might for your iOS, Android, iPad, and Watch apps).

Fourth, just look at all the UI's in WeChat! It is not the case that all the apps inside WeChat are messaging UI's. Quite the contrary, WeChat's Official Accounts and games are replete with unique graphics and user interface elements. Just because the container is a messenger doesn't mean that all the apps inside are text-based. (Similarly, just because we call it a "phone" doesn't mean that all the apps inside it are voice-based.)

GUI lives(!) inside WeChat

GUI lives(!) inside WeChat

So while I think there are good reasons for all the command-line-like interfaces that are popping up, I also think it's hyperbole to argue that broad services will be primarily text-based (as Magic and GoButler would seem to be argue). In fact, some of the reasons why people are building SMS- and messaging-based apps now are just flight from competition in the App Store, and that alone is not a great reason.

With respect to the App Store, Apple's grand bargain has worked: They snatched much of the control developers had on the open web in exchange for a marketplace that is so safe and so reliable that even your grandmother will install software. At a time when the inspectability of web software — one of the central tenets of the web's "openness" — is causing some upheaval in the form of ad blocking and user privacy, there is another an open, platform-agnostic protocol emerging in software development that not even Apple can control: human language. Natural language processing, however near or far away it may be, is one way that Facebook Messenger and other messengers can build "apps" that are outside Apple's purview.

One reason to welcome a future in which messenger-based apps are more conversational and more conventional in nature is that, like the websites being delivered to relatively homogeneous browsers, much of a messaging-based app lives on the server and could theoretically be deployed relatively easily to other messengers. There could be a rising-tide-that-lifts-all-boats effect in which apps and developers get trained up on the first dominant messenger platform (most likely Facebook) and then extend similar services to other messengers. (Even if payments are somewhat fragmented across Facebook-, Apple-, Google-, and Stripe-powered Buy buttons.) This future would have the messengers as the "new browsers", promising some relief from the hegemony we find ourselves in today.

Thanks to Joel Monegro for reviewing this post